Refugees: 8th grade students spend time in high school immersion experience

Junior Sarae Miguel opens the door and welcomes 8th graders to the Algebra 2 classroom.

December 13, 2019

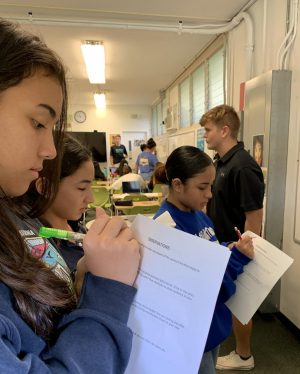

8th graders taking observations in Algebra 2 classroom.

Opening the door to a new environment, unknowing of what to come, three students were forced to step out of their regular classrooms, into one they knew nothing about.

Imagine being in eighth grade and suddenly thrust into an 11th grade math class. What would you do? How would you fit in?

This experience could be similar to the experience of a refugee to a new country. They may not understand the language, culture or be familiar with any of the surroundings.

To help students understand the experience of a refugee, Grade 8 teacher Kalei McDonnell planned a day where small groups visited a different grade classroom and had to explore into the different culture.

“I’m hoping that this immersive experience gives them a first hand feel for what it must be like to leave the comforts of your own class and then actually be forced to go somewhere where you’re not familiar with what’s going on,” said McDonnell.

Students had to figure out how to assimilate into their “country” and how they were going to contribute, McDonnell said.

Three eighth grade students entered an algebra 2 math class, taught by Michael Hangai. During the time they were there, two 11th graders gave the 3 eighth graders a mini math lesson.

One of the refugees, Norika Christian, said she felt nervous, but she remained attentive to the math lesson.

“I was a little nervous because you guys are older than us and it’s new to me,” said Christian.

The 11th graders were welcoming, nice and helped explain the problems thoroughly, she said.

After this experience, Christian said she understands and sympathize more with those who are forced to flee their homes.

“[Refugees] had to adapt to a new space that they have never been to and it’s sad because they had a home … and made memories with [their home] and now they had to go away from all the memories and happiness and they had to go somewhere that they don’t know,” said Christian.

“The central pillar on why I’m doing this project is to get students to be more empathetic for people that are different than they are,” said McDonnell.

High schoolers and teachers had to decide whether they wanted to invite the refugees into their classrooms. It enabled highschoolers to ask themselves, if they should let the new refugees in and why or why not, McDonnell said.

Hangai made the 8th grade students feel welcomed by making sure he smiled a lot, he said.

“I just made sure to walk up to each of them and tell them welcome to our class and I’m glad that they were here,” said Hangai.

Hangai said he wanted his students to make sure they included them in the work they were doing and to have the 8th graders participate.

One of the 11th grade mentors, Sarae Miguel, incorporated the 8th grade students into the work she was doing.

“I kept asking them if they were understanding and had any questions to make them feel more involved … and that creates a sense of involvement or that they’re welcomed into the classroom,” said Miguel.

In the real world, refugees from countries like Syria must flee their homes and this journey can be difficult, dangerous and scary, McDonnell said. McDonnell wanted her students to study and start to understand what this is like.

Not only do McDonnell’s 8th grade students take something away from this project, but the high school teachers and students as well.

“I do want the high school students to take away from this project a sense of “if I had the power, would I open borders or would I close my borders, how would I accept these new immigrants or new refugees and what implications does it have for my future,” McDonnell said.

McDonnell said she wanted to compare real world immigration issues to similar issues the students read in their novel for their immigration and refugees unit.

The book the students are reading,“Salt to the Sea,” focuses on refugees who are forced to flee Nazi Germany at the end of World War II.

McDonnell said she wanted to compare this example to the current state in the world with refugees fleeing Syria, Somalia and parts of Indonesia.

McDonnell said she developed this idea after her homeroom experienced a fleet students from other homerooms entering freely.

“My homeroom students started coming up with reasons why this person wasn’t allowed or why that person couldn’t come in,” said McDonnell.

Her students came up with a set of rules to apply for a “visa” to enter her homeroom.

McDonnell said she hopes the classroom visits will lead to increased understanding of refugees who have to leave their homes.

The United States plans to admit a maximum of 18,000 refugees in fiscal year 2020, according to the Pew Research Center. Since 2017, the United States has admitted about 76,200 refugees into the states.